Science, society, and the truth behind expert testimony

Hikers find a woman’s body in the woods. Decomposition has degraded all the muscle tissue above her waist, leaving nothing behind but bones, and even those have been scattered and picked apart by scavenging animals. Her wallet allows police to identify her. DNA samples later confirm her identity.

In the courtroom, the air is heavy with anticipation as the defendant waits for the verdict. He’s nervous; the prosecutor is too calm.

And the prosecutor is certain he’s going to win. DNA evidence places the defendant at the scene of the crime. The board-certified is confident that she had been strangled by someone who matches the defendant’s height and weight. The bite marks on her legs were definitely made by the teeth of a human male — again, with the same height and weight.

Most importantly, the expert witnesses he’s called have cited multiple prestigious studies to support each claim. Even if the jury isn’t swayed by the overwhelming amount of evidence against the defendant, surely hearing that research at Harvard and MIT supported the prosecution will convince them.

It doesn’t hurt that the news media camped out outside have driven themselves into a frothing frenzy this past week. There are lurid editorials about how this man — this big, tall man had allegedly, probably, definitely, crushed the windpipe of this poor, defenseless woman.. Nor does it hurt that the DA has tacitly encouraged their spin, intent on securing a conviction for the heinous crime that has gripped imaginations across the nation. After all, a case this public will guarantee his re-election.

The jury returns, and a verdict is handed down: guilty.

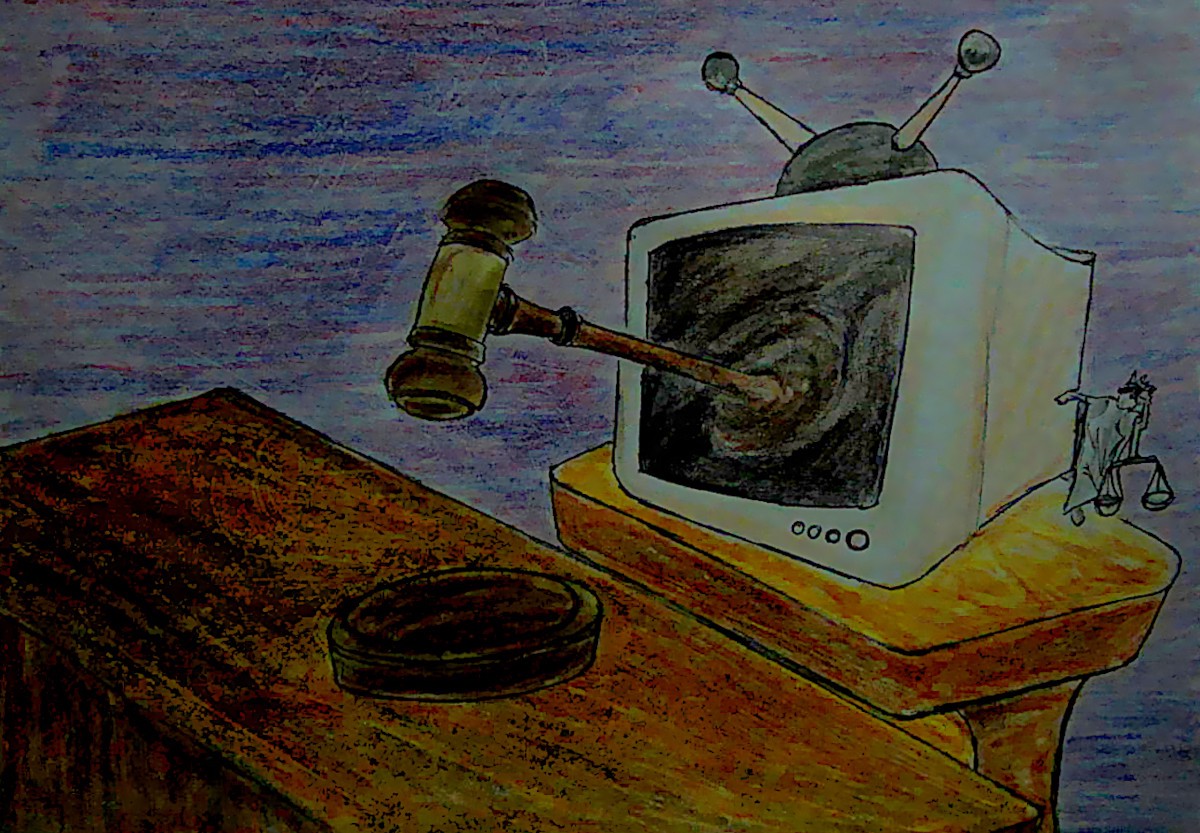

In legal circles, the CSI effect is the idea that the proliferation of police procedural and detective shows has made it so that jurors are predisposed to (wrongfully) acquit (guilty) defendants in the absence of biometric evidence like DNA and fingerprints. Jurors now expect real-life courtrooms to function like their fictional television counterparts, making it unduly difficult for prosecutors to prove their case.

Despite its popularity, many experts have called prosecutors’ definition “simplistic”. As research by Michigan judge-turned-academic Donald Shelton has revealed, peoples’ expectations about scientific evidence may not really affect how likely they are to convict someone when that evidence isn’t available.. As Shelton himself puts it, “differences in expectations about evidence did not translate into important differences in the willingness to convict.”

Shelton also believes that jurors’ increased expectations are not necessarily a bad thing. For him, increased technological and scientific literacy dovetails with the prosecutor’s burden of proof — the idea that a person is innocent until proven guilty. He explains that a biggest threat to the integrity of the jury system is social media. In particular, Shelton voices concerns about the spread of pseudoscience and social media’s ability to influence jurors’ beliefs.

It’s been a few years since the “woman in the woods” case was resolved.

Or was it?

A handful of tenacious journalists notice that the doctor, who conducted the autopsy, claims to be doing 1,500 autopsies a year. Suspicious, they begin to dig deeper.

When they get to the case of the woman in the woods, they turn up some disturbing information. The DNA evidence was brought to the scene by unwitting paramedics. The body was skeletonized from the waist up, so there was no way the doctor could have concluded it was strangulation. There is no scientific evidence that doctors can determine the height and weight of the assailant from the body alone. In fact, none of the scientific studies the doctor cited even exist.

Their most shocking realization? The “doctor” isn’t even really a doctor, let alone one certified by the National Association of Medical Examiners to conduct autopsies.

Why did no one notice any of these mistakes? Surely, the defense must have been able to round up a few expert witnesses to debunk the nonsense produced by the prosecution? As it turns out, the judge refused to allow the defense to call in any doctors or scientists of their own. Worse still, he had allowed the prosecuting attorney to claim that the absence of experts for the defense meant that his own expert was definitely right.

Now, this is a fictional scenario, but the details are all drawn from real cases — cases where miscarriages of justice led to innocent men being incarcerated, while the real murderers walked free. Each of these cases calls into question the impartiality and integrity of a system we’ve been raised to believe in as unimpeachably objective.

When we watch Law and Order or any one of the myriad CSI spinoffs, we see pathologists and scientists making definitive statements that help put the bad guys behind bars. We trust their expertise, their honesty, their skills.

But reality is often much murkier.

Scientists have a slightly different definition for the CSI Effect than attorneys. For them, the CSI Effect describes situations where jury members assume the tests and reports provided after post-mortem examinations are infallibly accurate. Their CSI Effect comes into play when jurors expect overworked and underfunded techs to be able to manifest results at a whim, under the misguided belief that they have access to much more sophisticated technology than they actually do.

You know the genomic analyser that the team in Bones invariably uses to conjure up everything from the body’s race to a reconstruction of its face? Spoiler alert: there’s no such thing.

This is a cause for concern, because the only thing more injurious than someone who doesn’t understand how the science works is someone who wrongly thinks that they do. There is a staggering level of scientific misinformation being disseminated through the internet and social media, as well as a disturbing lack of scientific literacy in the general population. What happens to the integrity of a legal system when jurors can’t even trust those who are supposed to be unbiased information providers?

Dr. Kristina Killgrove mentions how assessing ancestry and race using genomic data is far more complicated than many shows portray. Race is a social construct, so while osteologists might be able to provide a general geographic place of origin, they can’t necessarily predict the exact features or skin tone of the individual.

Also, allow me to state for the record that the entire idea that finger-length can be used to find the sex of a body is nonsense. For all the good science on the show, there are many moments where technicalities get glossed over for the sake of the story.

In reality, DNA samples are often shoved into ever-growing backlogs. Those that do see the light of the PCR machine can take days to process. Even then, it is possible that the tests used to analyze the sample are out of date, and less effective. There is also the question of whether the sample itself is contaminated, degraded, mislabeled or a partial construct that matches with multiple people,

The science behind DNA analysis is not as clean-cut as we might think it is. While it can be helpful in spotting genetic anomalies or identifying specific diseases the source of the sample might have, it falls far short of the miraculous solution it serves as in TV dramas.

Recent incidents have also raised ethical concerns tied to the databases law enforcement use to compare DNA samples. Some officials have surreptitiously uploaded suspect samples onto ancestry websites to identify people who had been at the scene of the crime. Others have created “shadow databases” that store genetic markers of innocent people and juveniles. These people often gave their DNA to officials for exculpatory or elimination purposes, so that their innocence could be proven in crimes that took place in their neighborhoods. They hardly expected that officials will store these samples for use in future cases, or that they might then be wrongfully convicted by virtue of their presence in the system.

And that’s not all. A 2014 internal review found evidence of typographical and interpretations errors committed by lab workers in the NY state database. Other states likely have similar issues, but the lack of standardized review protocols and reliability testing makes it difficult to know the scope of the problem. There is a lack of oversight, one that is, again, exacerbated by underfunding and the increasing outsourcing of forensic analysis to private contractors.

Human error is not limited to DNA sample collection and processing. There are also plenty of cases of scientific misconduct and mishandling of evidence. Pathology facilities are criminally underfunded (pun intended), to the point where many county coroners cut corners on autopsies, even going so far as to cut autopsies out of the post-mortem examination entirely. Along with allowing possible homicides to slip through the cracks, this hurts public health agencies’ ability to head off epidemics. After all, autopsies and the work of pathologists was integral to spotlighting the effects of the opioid crisis. What other threats to public health will go unexamined as autopsy rates continue to fall?

As with everything else, it is important to remember that these autopsy and test outcomes are only as good as the person conducting them.

The loss of oversight that occurs when analysis is outsourced to private firms also plays a role in this. Take the case of Thomas Gill. Despite being demoted and eventually fired from position in the LA county coroner office for shoddy autopsy work and workplace intoxication incidents, he has simply moved into the private sector, where he continues to oversee and conduct autopsies in criminal cases.

If that isn’t horrifying enough, take the scandal-ridden career of Steven Hayne. He has repeatedly given unsubstantiated, unscientific testimony, basing his reports on pseudoscience peddled by the likes of Michael West. West himself was also the subject of multiple investigations — his “bite mark” theory has been repeatedly criticized for fraudulent science that collapsed under scrutiny.

One of the reasons liars like this continue to be given credibility by jurors is because of their bad science. Proper scientists will preface their statements by saying “the data suggests…” or “this paper demonstrates…” They will never** **say that something is “proven” or make such definitive statements.

But bad scientists will, because they don’t care about the science. They care about convincing jurors and convict the defendant, even if it means throwing everything they should stand for under the bus.

Remember how all those SAT prep books told you to watch out for answers that used words like “all”, “definitely” or “absolutely”? Those are definitive statements, and they should be ignored just as much when made by pseudoscientists on the stand as when they show up in multiple choice questions.

Unfortunately, defendants might not have access to experts who can counter the fallacious nonsense espoused by such charlatans. While state and county prosecutors have access to taxpayer money to fund all the “experts” they want, defendants often have to rely on overworked public defenders who might struggle to access equitable resources. States spend considerably more on their prosecutors than their public defenders, as case closures and convictions make them look more successful and improve politicians’ chances of re-election.

As David Carroll, executive director of the Sixth Amendment Center, puts it, “There is no greater tyranny than a well-resourced prosecution and law enforcement when individuals don’t have a proper defense.”

Crime shows and police procedurals are one of the biggest constants in the American media landscape. Ever since Man Against Crime debuted on American televisions in 1949, the inner workings of the country’s crime-scape have captivated viewers and readers alike. Crime and thriller novels continue to be one of the best-selling genres, while True Crime and police procedurals are an ever-present staple in our media diets.

Last year, in the wake of America’s ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests, many police procedurals and crime dramas came under fire for inaccurately representing the contentious reality of America’s criminal justice system. But scientists have been debating the accuracy and validity of these shows long before. While the genomic analysis device in CBS’s Bones’ is one of the more obvious offenders, many of these shows tend to play fast and loose with science in pursuit of a good story.

Some shows might overplay the accuracy and integrity of the methods shown in order to neatly wrap up the narrative in under an hour. Others might cut corners on the protocols that real-life criminal justice professionals have to follow. And some might just make-up science and technology for easy plot resolutions.

Either way, the CSI Effect is a tangible outcome of fictional media that’s impacted the very real lives of very real people. Jurors need to be made aware of the contexts in which autopsies and tests are done, as well as the science behind their results. We need to institute better science education that teaches people about the importance of error rates and the evils of absolutism, so that they can be better informed when they have to weigh someone’s future in their hands.

So the next time you read a sensationalist crime headline in the newspaper and find yourself passing judgement, ask yourself: how much do you really know?