Battle simulation, allegory, romantic pursue, and ‘the Immortal Game of 1851’.

The soldiers advance, their line uneven but holding. Knights collide in tremendous fashion, forcing the enemy back, while reinforcements sweep quickly across the battlefield, pinning them down. Rallying around their queen, the army moves in unison, ready to strike the killer blow. The enemy king retreats, but falters — and suddenly, it’s all over.

It’s difficult to think of chess today and not feel a little intimidated. The game is dominated by geniuses and computers to such an extent that learning to play it can be daunting for all but a few of us mere mortals. But chess has been many things in its long and storied life, and it was once so much more than a mere logical strategy game.

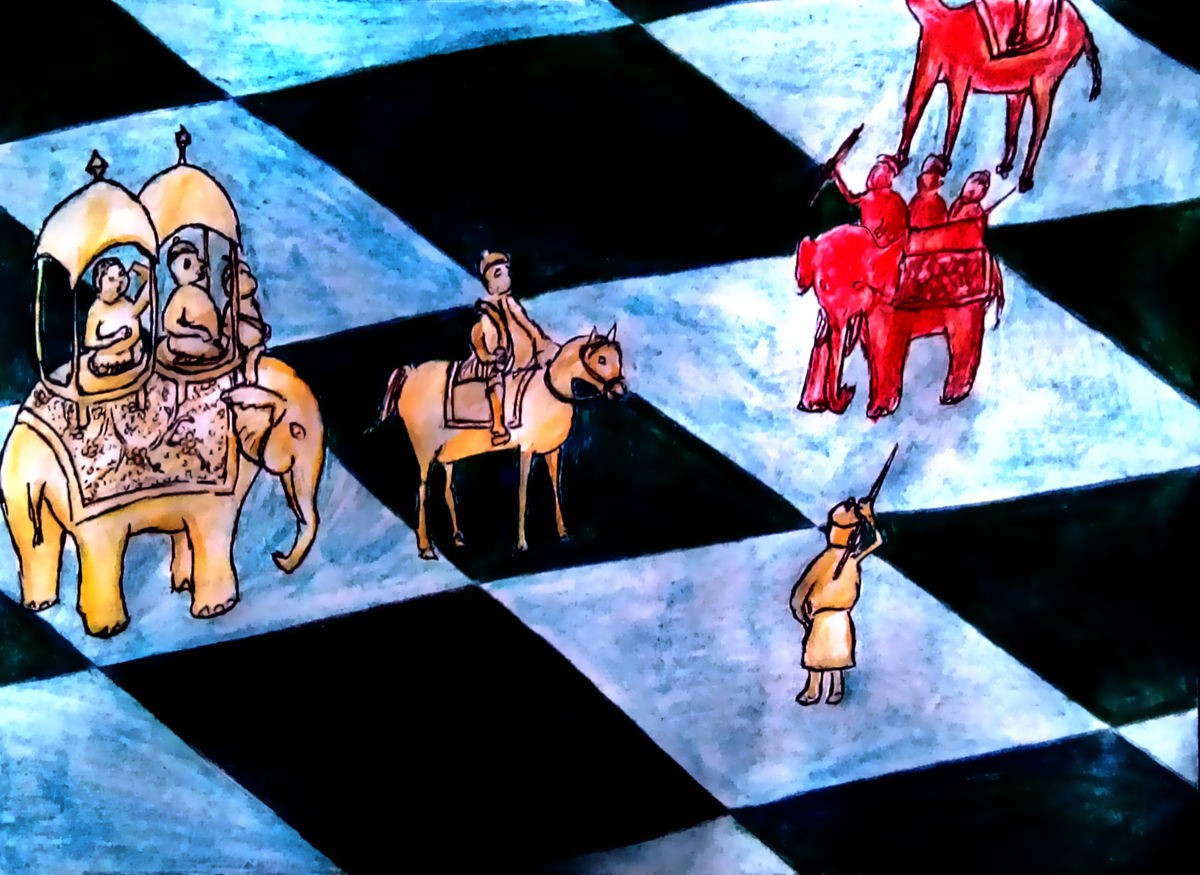

The origins of chess are divisive, to say the least. The first written sources come from Persia following the Islamic conquest of the area in the 7th century. Legendarily though, chess was created a century earlier in the Gupta Empire, in what is today India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, as a means of explaining the death of a young prince his grieving mother. The game was then known as ‘chataranga’, which means ‘four dimensions’ in Sanskrit and is a reference to the board used at the time.

From there it journeyed to the Sassanid Empire, where it became popular with the empire’s rulers. The word ‘chess’ also comes from this period, evolving from the word ‘shah’, meaning ‘king’. Checkmate, or ‘shah mat’, also originates here and originally meant ‘the king is helpless’.

At this time chess, was almost exclusively a battle simulator for the rulers of these lands and their commanders. Chess was used to hone the mind and develop attack strategies but was rarely played purely for pleasure.

That all changed with the Islamic conquests of the region in the 7th century. While still an exclusive game for elites and scholars, it began to be seen less like a battle simulator and more as a creative game, even taking on allegorical undertones when it was used to demonstrate political power and hierarchy within society.

Like many of the best and worst things in history, chess soon spread across the Medieval world via the Silk Road, spawning many regional variants. Shogi, also known as Japanese Chess, is one of the most complex variants of traditional chess, its biggest difference to modern chess being that captured pieces join the opposing side. Xiangqi, or Chinese Chess, is another regional variant from Asia that remains incredibly popular in China to this day.

By 1000AD, what we would recognise as chess started to truly take shape. Chess became part of courtly education: it was used to demonstrate the idea of people performing their proper duty and living up to the social expectations of the time. This would also be the period where many of the rules were standardised into those roughly resembling what we know today.

By the beginning of the Renaissance, the ‘queen’ had been introduced,. This fast-moving piece quickened the game’s pace dramatically, which in turn gave rise to some of the first treaties on ‘chess theory’.

Widespread as it was, chess was for a long time an upper-class pursuit. It would not be until the Enlightenment that chess left the palaces, courts and estates of the nobility and began to spread among the cafes and coffeehouses of the urban commoners. The game was steadily growing in popularity during this period, but it would find true success as a ‘Romantic game’ in the latter part of the 18th and early 19th century following the Enlightenment.

During this time an artistic and cultural movement was sweeping Europe, focusing on demonstrations of emotion, drama and individualism. It was known as ‘Romanticism’ and drew heavily from the Medieval era, as opposed to the Enlightenment’s focus on the Classical world. A great many famous poems, novels and artwork come to us from this period, including those of Wordsworth, Byron, Goya and Blake, but in terms of chess it also created a revolutionary reinterpretation.

Chess with its kings, queens, knights and strategies was a perfect allegory for emotional sacrifice and passion, and a style of chess was born that would frankly seem alien to us today.

Romanticism was set against a tumultuous time in Europe. The French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars turned culture on its head and while kings and queen in the real world fell out of favour, on the chessboard they played out dramatic narratives of loss and sacrifice that resonated with romantics of the time.

The chess of the 19th century emphasised creativity over logic; it encouraged boldness and drama rather than strict adherence to strategy.

All of this culminated in what is perhaps the quintessential game of ‘romantic chess’ — the immortal game of 1851. Played in London between Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky, this informal game would be received very differently today. Adolf Anderssen, a great chess player of the day, sacrificed both his rooks, a bishop, and his queen to capture Kieseritzky’s king with only minor pieces.

The game focused on speed and passion as a strategy and when viewed from our modern understanding, Kieseritzky appears to have played the better game despite his loss, but it exemplifies the standard of the time. When viewed with a more artist eye, however, it takes on a different appearance. Anderssen carves a bloody path through his adversary and though he loses all those dear to him (the chess pieces), he forces Kieseritzky’s hand and ultimately triumphs.

When understood like this, the story reads more like a heroic play, than a game of chess.

While chess is no longer a romantic game, now being the realm of machines and tactical geniuses, it’s important to remember that chess has always been a game of allegory. Most games we play are based around chance, but chess, along with many other strategy games, draw on our unique, human creativity.

Chess then is ultimately a reflection of those playing it. It began a battle simulator for kings and commanders, before spreading across the world and coming to represent the strict social hierarchy of the Middle Ages. From there it spread to the common person, inspiring them to think outside the box in an age of unprecedented change, before finally it was taken up by the romantics, who saw in chess a lost sense of purity and passion from the medieval world, playing out stories and epic scenes on the 8×8 board.

Chess will likely continue to evolve in ways we cannot yet to imagine. The game is reflective of those playing it and the world that will birth new generations of chess players and new styles of play has yet to be made. The only thing likely to remain the same is our boundless love for one of the world’s favourite games.